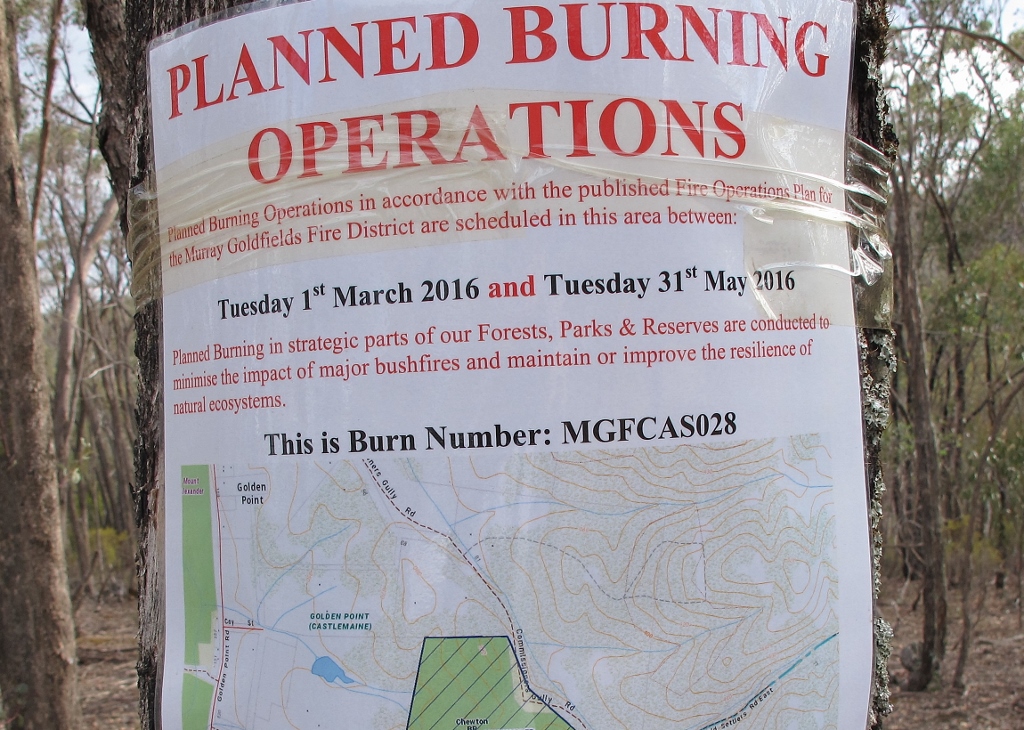

The 2024-5 bushfire season has started in Victoria, so it might be a good idea to draw attention to one important dimension of management practices. Readers will no doubt be familiar with this kind of notice, attached to trees to notify the public of an upcoming burn:

Note the objective ‘to maintain or improve the resilience of our natural ecosystems.’

Is that objective being achieved? Is it even a serious objective? Whenever we’ve enquired about the purpose of a particular burn, the objectives given to us are to do with life and property, and any mention of ecosystems is vague in the extreme. Some fire officers have expressed outright cynicism about the stated objective!

Now, a new study of the Black Summer fires of 2019-20 suggests that in those fires the most serious damage to biodiversity occurred in areas which had most recently burned:

The study, in the journal Nature, ‘found that sites with high fire frequency (three or more fires in the 40 years preceding 2019–2020) had negative effects that were 87–93% larger compared with sites not burnt or burnt once over the same period. Similarly, when the most recent inter-fire intervals were short (10 years or less), negative effects were 70% larger compared with sites burnt more than 20 years previously.’ These effects were observable even when the previous fires had been mild.

The study also found that frequent fires strongly favour some species. This could lead to the dominance of fire tolerant species and a rapid decline of species more seriously affected by fire. Serious fire also favours feral predators able to move more freely in post fire landscapes.

The study ‘observed the smallest effect sizes at intermediate fire intervals (11-20 years), indicating that communities undergo the least disruption at these intervals. Long intervals are also needed to serve as refuges, create time-dependent habitat attributes such as tree hollows, and support source populations for species that might be lost from areas burnt too frequently.’

(It’s worth noting that, according to a 2010 study by David Cheal, the minimum tolerable fire interval in box/ironbark forests is 12 years after a low severity fire and 30 years after a high severity fire.)

The authors of the study accept the need for fire management action to protect both forest and people: but they urge a change in current strategies: ‘ Given that under extreme weather, prescribed fires have limited capacity to prevent vulnerable areas from burning, widespread and frequent prescribed fire is a poor choice for responding to the growing fire threat. With such a vast area of Australian forests in an early post-fire state, increasing rapid wildfire suppression is now an important alternative strategy for limiting short fire intervals.’

There are, of course, other factors driving fire severity, like drought; and long term warming is an overarching reality, something we feel every summer. The study factors these realities into its findings. It would be good to think fire officers—and maybe more importantly, politicians—are giving it a good look.

Click on image for info/order page

Click on image for info/order page Click on image for info/order page

Click on image for info/order page Click on image for info/order page

Click on image for info/order page

…thanks for sharing this study, it removes one more myth about planned burns being that they can a protect flora and fauna.

The David Cheale minimum tolerable fire interval considers only flora. If fauna were also considered , the minimum tolerable fire interval would be much much longer.

I agree. In their ecological burning study in 2007 Arn Tolsma David Cheal and Geoff Brown say of birds, for example: ‘species that rely on the ground layers for nesting or foraging may be disadvantaged in the short-term by low-intensity fire, particularly if it interferes with breeding. The minimum inter-fire period is likely to be similar to that which will allow full recovery of understorey structure (i.e. at least 25 years).’