Loddon River, Baringhup

A good attendance of interested walkers met at the farm of Kerrie and Rob Jennings for an Easter Sunday wander along the Loddon River. In this dry time, the sound of running water seemed almost unfamiliar! This is due to the release of water for irrigation from Cairn Curran Reservoir upstream. As we made our way along the river, Barry Golding weaved stories of geology and history, drawing from his recent book, Six Peaks Speak, revealing the environmental and cultural significance of this place. At the same time, we encountered Easter campers and heard the occasional gunshot of duck shooters.

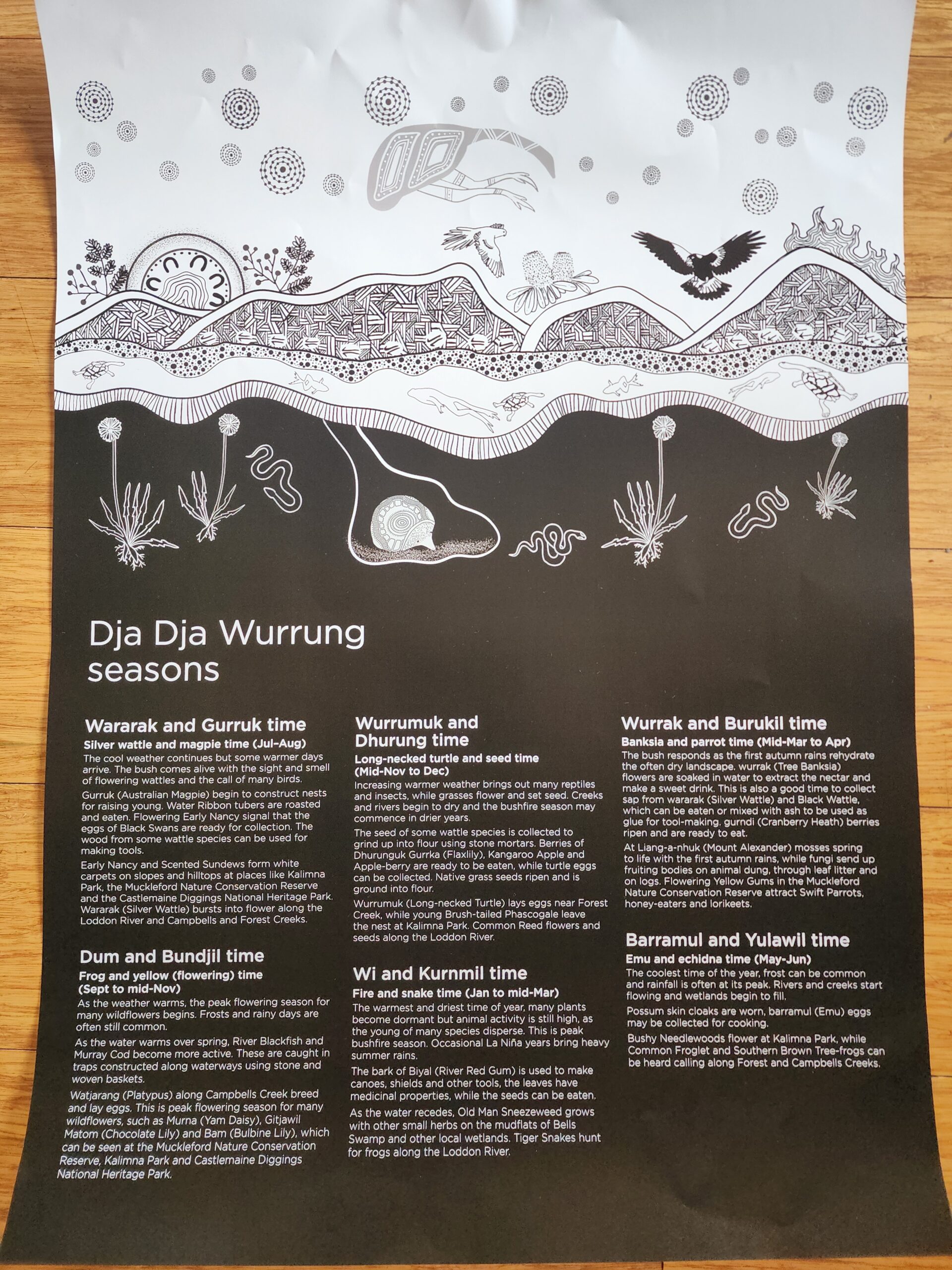

There were stunning stands of old river red gums and at the end of the walk near Hamilton’s crossing, where we stood with a huge ring tree. The striking high cliffs of red sand, known as ‘Redbank ’, is where the Loddon takes a dramatic turn to the west. Barry explained that this is where the river the meets hornfels, a very hard rock on the edge of the granite. Above Redbank was the site of Victoria’s first Aboriginal protectorate. There were numerous quartz fragments on the ground that are produced in the manufacture of Aboriginal tools.

In an Acknowledgment to Country, First Nations woman, Jane Harrison, reminded us of the importance of walking with Country. We walked, listened, shared and learnt.

Thanks to Joy Clusker for additional photos

Click on image for info/order page

Click on image for info/order page Click on image for info/order page

Click on image for info/order page Click on image for info/order page

Click on image for info/order page